“The greenery and the feeling of space can be felt in every room and at every front door.” (1)

The green spaces in the Hansaviertel of Interbau

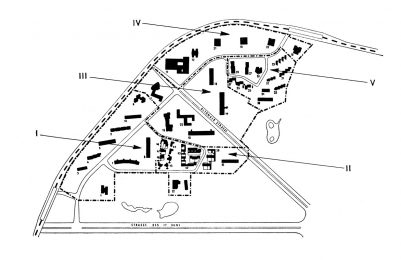

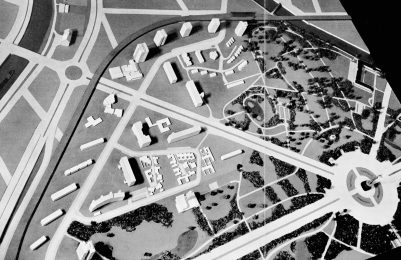

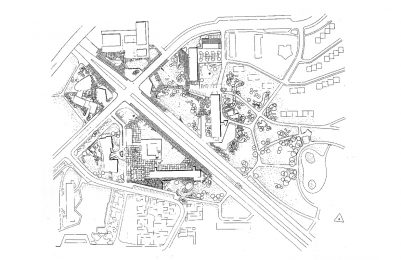

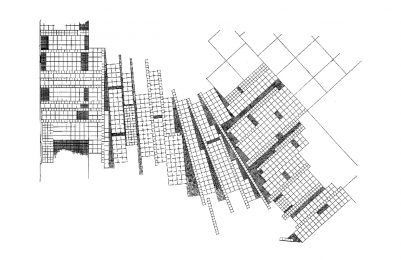

For the urban architecture of the Hansaviertel, the green spaces are as fundamental as the buildings themselves. Indeed, they were an integral feature in the winning plans in the Ideas Competition for the Reconstruction of the Hansaviertel in 1953, won by Gerhard Jobst and Willy Kreuer, along with Wilhelm Schließer. In a radical departure from the “stone city” structures typical of the imperial era, consisting of dense building developments and narrow alleyways, the architects proposed a Hansaviertel that was extensively landscaped. By building upwards on a small surface area, Jobst and Kreuer’s design reduced the area physically taken up by the building, thereby making large open spaces possible. The borders between the residential areas and the green area of Tiergarten were dissolved so that both could merge into each other, and the architects positioned the proposed high-rise buildings in two “bays” opening up onto Tiergarten. In addition, in the final layout of the Hansaviertel, a drop in height of the buildings towards Tiergarten and the wide spaces between the buildings allowed the green to enter into the residential area. While the ratio between built-up areas and green spaces was 1 to 1.5 in the old Hansaviertel, a ratio of 1 to 5.5 was achieved in the new Hansaviertel.

Section I by René Pechère (1908–2002) and Hermann Mattern (1902–1971)

Section II by Otto Valentien (1897–1987) and Ernst Cramer (1898–1980)

Section III by Herta Hammerbacher (1900–1985) and the Swede Edvard Jacobson (1923–1986)

Section IV by Gustav Lüttge (1909–1968) and Pietro Porcinai (1910–1986)

Section V by Wilhelm Hübotter (1895–1976) and Carl Theodor Sorensen (1893–1979)

To have modern designs of the highest quality for the open spaces, the Senate commissioned five teams, each team being responsible for one section and consisting of a German and an international garden designer. Sitting on almost every committee of Interbau, the landscape architect Walter Rossow (1910–1992) played an important role by advocating that the planning of the landscape and the planning of the buildings should be of equal importance. Time and again, Rossow pointed to the discrepancy between the motto of Interbau – “people in a green metropolis” (2) – and the lack of a dedicated landscaped design for the Hansaviertel. In a 1955 article “Green Spaces in the Hansaviertel” (3), Rossow called for the close collaboration between the structural architects and the landscape architects during the design phase, and at his insistence the steering committee decided to involve landscape architects in the planning of the Hansaviertel. The teams of garden designers eventually started work at the beginning of 1956 (4), though only after the layout had been completed and after most of the buildings had been designed.

As a guide for the landscape architecture, Rossow stated that the green spaces should neither be decoration, nor should they be “romantic landscapes”. Rather, spaces should be created out of the “freely and openly positioned houses and trees, and in the transition towards the parkland” (5) of Tiergarten. Moreover, a “visible connection between the outside and the inside” (6) should emerge. Otto Bartning also pointed out that the green spaces should be made “pleasant for the residents and their children” (7), a requirement which was widespread in the 1950s and which was also advocated by the landscape architect Hermann Mattern in his book “Die Wohnlandschaft”. (8)

At the same time, the green should enter into the houses, for example by having the courtyard gardens of single-family homes act as a “green room”, which was realized in the atrium and courtyard houses of the Hansaviertel. Efforts to dissolve the borders between the green areas and the buildings are also apparent in the slab buildings of the quarter. For example, Oscar Niemeyer’s elevated apartment block on Altonaer Straße allows views into the green and guides the open space through the building. Shared spaces are divided up through the modelling of the ground, pathways with different paving and the installation of trellis fences and seating. In the larger green areas, individually placed tall trees, ornamental shrubs and connecting paths form the transition into Tiergarten.

An outstanding example of this is the design of Hansaplatz by Herta Hammerbacher, who was the only woman among the landscape and building architects involved in the creation of the new Hansaviertel. Largely undefined by architecture, the vast square was planted with tall-growing trees, which appear to be randomly arranged, looking like they have always been a part of Tiergarten. An organically laid-out path system unobtrusively gives structure to the large grassy areas of the square. Partly made out of customised slabs, the laying pattern of the paving on the square was particularly admired. In some places, irregular shapes are created by gently radial patterns made up of light and dark concrete slabs and Bernburger crazy paving reaching out into the grassy areas. As this surface covering features only in certain areas of the vast square rather than over the whole area, it appears as though the paving flows through the residential area, just as the green area of Tiergarten flows through the housing development. Moreover, this paving pattern unites the residential area. This is particularly successful at the corner of Altonaer Straße and Klopstockstraße, where the pattern continues on the corresponding side of the road, optically connecting the different parts of the square. Hammerbacher thereby integrated the design of the green areas with the town planning and architectural guiding principles of Interbau.

Dr. Sandra Wagner-Conzelmann