“You had to have stood on the burnt-out wasteland of the Hansaviertel in the spring days of 1945, you had to have seen the sight of the deforested Tiergarten torn to shreds to recognize this positive development. Because the re-grown Tiergarten, just like any new house, is a sign of the city’s will for the future …!”

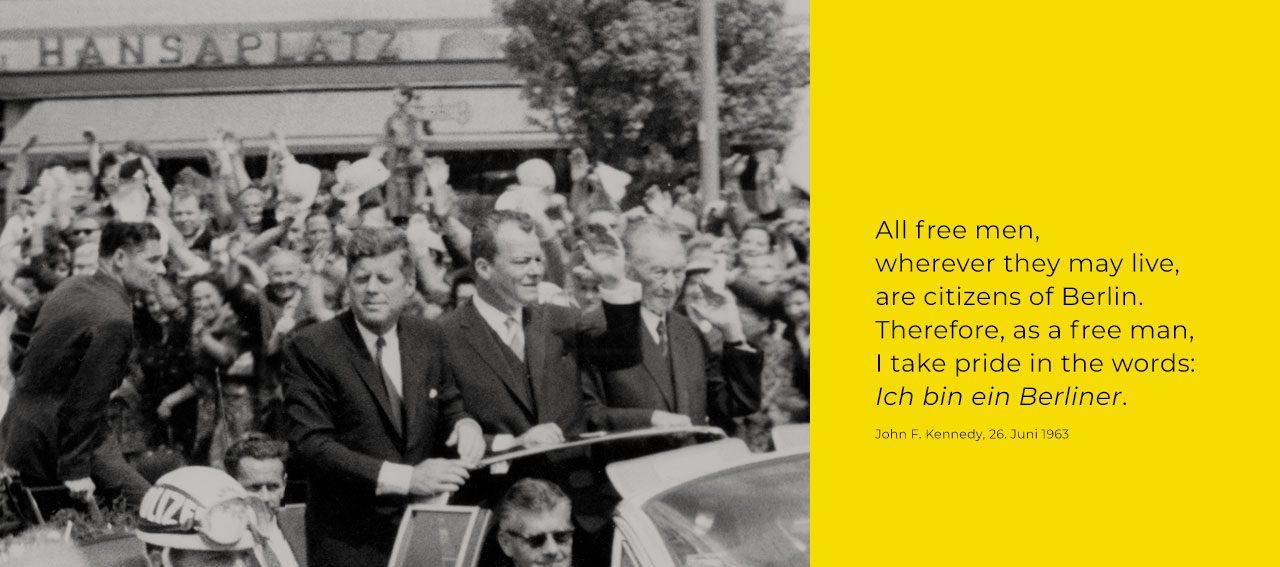

With these words, Otto Suhr, Governing Mayor of Berlin, welcomed the participants to the opening of the Interbau exhibition in 1957 in Schloss Bellevue. He was certainly expressing the feelings of many Berliners.

The Hansaviertel was almost completely destroyed by bombing raids, particularly after 1943. Of the 343 buildings, about 300 lay in ruins at the end of the Second World War, and the rest were badly damaged.

As an inner-city expanse of rubble, the Hansaviertel was to become a symbol of Berlin’s will to renew itself. In 1952, 53 architects from 13 countries were invited to take part in a competition. All of the architects were advocates of the modern western ideas of “Neues Bauen” (“New Building”), including Alvar Aalto, Werner Düttmann, Egon Eiermann, Walter Gropius, Arne Jacobsen, Oscar Niemeyer and Max Taut, as well as the Dutch architectural firm Van den Broek & Bakema. In 1956, the Hansaviertel was redeveloped according to their designs.

The construction of the Hansaviertel was based on the ideas of modernism at the time. It was not a reconstruction of the old ruins; instead, new buildings were constructed. A total of 159 old plots were completely redivided, and the road and supply networks were changed considerably.

Interbau 1957 brought together the “Who’s Who” of the international architecture scene in the Hansaviertel. Here, buildings were designed to give the citizens of a new democratic society a home.

It was at the same time a reaction to the construction of Stalinallee (later: Karl-Marx-Allee) in East Berlin’s Friedrichshain district, which began in 1952 and whose architecture was based on Soviet monumental architecture. This was to be contrasted with an emphatically international and modern cityscape in West Berlin. The invitation of architects from countries that just a few years earlier had been wartime enemies was also to be understood as a gesture of reconciliation.